The Anti-Greeks

Alexandra Mavraeidi

1/9/20255 min read

Ancient Greece is often celebrated as the cradle of democracy, philosophy, and the arts, with a society seemingly homogenous and bound by enduring ideals of heroism, order, and tradition. Yet, beneath this cultural facade lay a world as diverse and complex as our own, where not everyone fit neatly into the mold prescribed by their times. From slaves who defied the odds to attain wealth and freedom, to poets who rejected the glorification of the battlefield, ancient Greece was shaped by individuals who broke away from the constraints of convention. This article explores some of these remarkable figures, whose lives and choices challenge our perceptions of what it meant to be Greek in the ancient world.

Archilochus

Archilochus occupies an important position in the history of ancient Greek verse. Born in the 7th cent. BC to a slave of a notable family on the island of Paros, Archilochus remained poor and served as a soldier, battling the indigenous Thracians on Thasos, despite his high origin.

His poetry, which consists of short poems of mostly iambs and elegies, contains harsh language, fiery verses, and insults, making him an archetypal poet of blame. In his works, Archilochus reveals his personality in all its defects without concealing discreditable facts. This was something that was highly disapproved amongst the people of his time. In one of his elegies, the poet even challenged the exaggerated notion of honour and heroism of the Archaic period.

waste one's life for an inanimate possession. Archilochus is no military coward; rather he is a realist, a challenger of aristocrat values and the warrior ethos of Homeric epic poetry. He is not actually presenting his retreat as an act of cowardice, nor is he shamelessly dismissing his action. Rather the poet comically humanises the heroic ideal by presenting a soldier that was engaged in something private behind a bush and was taken by surprise on the battlefield.

His verses about fleeing from a battle and leaving his shield to the enemy were considered so dangerous by the Spartians that they ordered his poems to be banished from their city.

ἀσπίδι μὲν Σαΐων τις ἀγάλλεται, ἣν παρὰ θάμνωι,

ἔντος ἀμώμητον, κάλλιπον οὐκ ἐθέλων·

αὐτὸν δ᾽ ἐξεσάωσα. τί μοι μέλει ἀσπὶς ἐκείνη;

ἐρρέτω· ἐξαῦτις κτήσομαι οὐ κακίω.

Someone of Saioi is reveling in my shield, which I discarded by a bush,

an undamaged weapon, unwillingly;

But I saved myself. Why should I care for that shield?

Let it go. Some other time, I'll get another no worse.

(Archilochus 5 West)

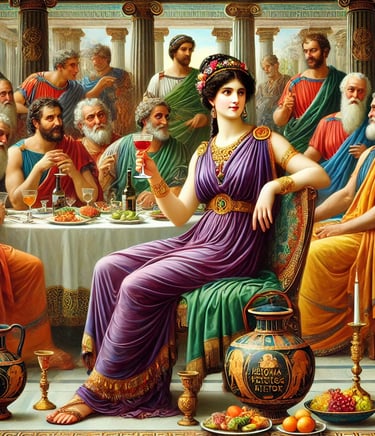

Gnathaena

Gnathaena was a famous hetaira (courtesan) of ancient Athens, renowned not only for her beauty but also for her wit and biting humor. She lived during the 4th century BC and was known to entertain prominent figures of her time, including philosophers, politicians, and poets.

Heterai were different from common whores (πόρναι). Their social skills and personality were the secret weapons in their arsenal, as successful heterai were noted for their excellent conversational skills and musical talents. They also enjoyed a degree of independence, since they had a social and sexual liberty unlike any other Greek woman whose role as a wife made her a servile object of compulsion, bound to necessity and the production of offspring in the seclusion of their home.

And so, Gnathaena was sought after by wealthy and influential

Unknown Pallake

In 5th century BC Athens slaves were a common sight. These socially dead people whose lives and rights were never recorded were taught to remain loyal to their masters despite their poor living conditions or the inhumane treatment they received. A slave who confronted her fate and took matter in her own hands was a pallake living in Peiraeus.

In Antiphon's narrative (Against the Stepmother for Poisoning), a pallake of an Athenian named Philoneus becomes a pawn in a vengeful conspiracy. After years of their companionship, Philoneus grows tired of her and intends to sell her to a brothel. The mother of Philoneus’s friend learns about his intentions and, motivated by personal grievances, befriends the pallake and reveals to her the plans of her master. Desperate to win him back, the pallake follows the mother's instructions and administers what she thought was a love potion to Philoneus during a sacrificial feast but which in reality is poison. Manipulated into believing the poison would secure Philoneus’s love, the pallake carries out her plan, with tragic consequences: Philoneus dies instantly. The pallake, even though ignorant of the true nature of her actions, is interrogated upon the wheel and is handed over to the executioner.

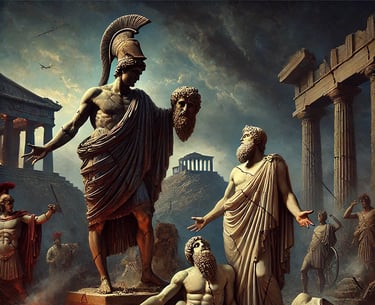

Andocides

Andocides, an Athenian orator and politician of aristocratic ancestry born in the late 5th century BC, became infamous for violating ancient Greek notions of piety and respect for the gods. In his time, the Herms were sacred statues of Hermes placed throughout Athens, particularly at crossroads and private homes, to protect travelers and bring good fortune. On the eve of the Sicilian Expedition, many of these statues were found mutilated. This act was considered a grave offense against the gods and an omen of disaster. Andocides was found to be implicated in this scandal. Although he tried to deny direct participation, he finally confessed under pressure, claiming to have knowledge of the perpetrators. His testimony was seen as an attempt to gain immunity, but it implicated him in violating the sacred and civic duty to honor the gods.

men in symposia where she was celebrated for her ability to hold her own in conversations with intellectuals and statesmen and held sumptuous feasts herself, defying societal norms and expectations and carving out her own identity in the male-dominated society of Athens.

To make matter worse, Andocides was soon accused for his blasphemous actions once more. Andocides participated in private reenactments of the Eleusinian Mysteries that were dedicated to Demeter and Persephone, as a profanation of their secrecy and sanctity. Such actions were not only a personal offense but also seen as a threat to the collective piety of the city. As a result, he was ostracized for these transgressions and spent much of his life in exile, as the Athenians sought to preserve their relationship with the gods and avert divine wrath.

Clearly enough, Andocides’ actions were seen as a blatant disregard for the religious customs and societal norms that upheld the moral and spiritual fabric of Athens. His story

exemplifies how deeply interwoven religion and politics were in ancient Greece and how acts perceived as impious could have both personal and civic repercussions.

Further Reading

Garland, Robert. Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks. Greenwood Press, 1998.

Adkins, Lesley, and Roy Adkins. Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece. Updated ed, Facts On File, 2005.

Briggs, Ward W., editor. Ancient Greek Authors. Gale Research, 1997.

Hazel, John. Who’s Who in the Greek World. Routledge, 2002.

Kivilo, Maarit. Early Greek Poets’ Lives: The Shaping of the Tradition. 1st ed., vol. 322, Brill, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004186156.i-272

Kapparis, K. A. Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World. 1st ed., De Gruyter, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110557954

Allison Glazebrook, Madeleine M. Henry. Greek Prostitutes in the Ancient Mediterranean, 800 BCE–200 CE. 1st ed., University of Wisconsin Press, 2011.

Fried, Lisbeth S., and Ruth Scodel. “Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World. Edited by Stephanie Lynn Budin and Jean Macintosh Turfa.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 140, no. 4, 2021, https://doi.org/10.7817/jaos.140.4.2020.rev066.

This elegy is a rejection of the warrior ethos in favour of self-preservation with the poet claiming that it is better to survive to fight another day than to